RESEARCH ARTICLE. Post by Paulo Duarte

Flávio Bastos da Silva1,2 | Paulo Afonso B. Duarte1,3

1Research Centre in Political Science (CICP), University of Minho, Braga, Portugal | 2Centre for Legal, Economic, International and Environmental Studies (CEJEIA), Lusíada University, Lisbon, Portugal | 3Centre of Advanced Studies in Law Francisco Suárez, Lusófona University, Lisbon, Portugal

Correspondence: Flávio Bastos da Silva (flaviobsilva2000@gmail.com)

Received: 12 December 2024 | Revised: 12 March 2025 | Accepted: 10 April 2025

Keywords: Belt and Road Initiative | Brazil | digital infrastructure | Digital Silk Road | digital sovereignty | security

ABSTRACT

Given the scarce studies on the security issues raised by the Digital Silk Road (DSR), we aim to add novelty regarding the repercussions of this dimension of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by focusing on the case of Brazil. As a major Latin American nation with strong ties to China, Brazil is an extraordinary case study when it comes to assessing the effects of any BRI-related dimension. Despite Brazil’s reluctance in officially joining the BRI, Brazil became part of the DSR after signing a Memorandum on the Digital Economy with China in 2023. By claiming that traditional liberal frameworks are insufficient to grasp the complexities of the digital space, we propose that the DSR is best approached through the lenses of Digitalpolitik. Based on a qualitative methodology complemented by an online survey and pre-selected interviews, we find that the initiative strengthens Brazil’s digital ecosystem but poses security risks to its digital sovereignty.

1 | Exploring the Digital Silk Road: Context, Gaps, and the Case of Brazil

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was announced by Xi Jinping in 2013 as a project capable of connecting logisti- cally and commercially China with the rest of Eurasia (China Daily 2013). This initiative was incorporated into the text of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China in the same year (Xinhua 2017a). Initially designed with two corridors—the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR)—the BRI quickly expanded into new regions such as Latin America, supported by a new corridor called the Digital Silk Road (DSR) (Halsall et al. 2023; Tomé 2023).

Since the launch of the BRI, several studies have focused on the SREB (Dave and Kobayashi 2018; Makarov and Sokolova 2016), as well as the MSR (Chang 2018; Zhu et al. 2019). Nonetheless, the literature regarding the DSR and its geopolitical, geoeconomic, and security effects is relatively scarce. Exceptions include the works of Parzyan (2021), Caridi (2023), and Sciacovelli (2023).

Recognizing the DSR as part of the BRI and a tool for advancing Chinese national interests, this paper examines its geopolitical and security repercussions in Brazil. While Brazil is not formally part of the BRI, it stands as one of China’s most successful Strategic Partnerships due to its size, population, resources, and longstand- ing ties with China. These factors make Brazil an exceptional case study in Latin America and among developing countries for assess- ing BRI-related initiatives. Despite Brasília’s reluctance to formally join the BRI, we argue that Sino-Brazilian cooperation in political, economic, and security domains is as advanced, if not more so, than in many BRI member states. In fact, we argue that although Brazil is not (yet) a BRI member state, it became part of the DSR after signing the ‘Memorandum of Understanding on Strengthening Cooperation in Investments in the Digital Economy’ with China on 14 April 2023. This position is supported by China’s continued investment in Brazil’s digital sector, as well as the signing of new agreements following this MoU. Furthermore, it is substantiated by other studies which, based on similar cases, suggest that such a memorandum typically signifies a country’s alignment with the DSR—a point we will explore in greater detail in later sections.

© 2025 Durham University and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Global Policy, 2025; 0:1–14 https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.7002

Policy implications

• Given the increasing foreign investment in the digital sector, Brazil may face risks related to its digital sovereignty, and therefore must prioritize the protection and security of its critical digital infrastructure.

• Closer ties with China and participation in the DSR could negatively impact Brazil’s relationship with the United States, so Brazil should seek to balance its co- operation with China while maintaining its relation- ship with Washington.

• Brazil should be aware that, despite the development benefits, DSR could serve a perceived revisionist inter- est of China, with associated risks.

• Emerging powers, particularly in Latin America, must remain attentive to China’s advances and digital investment, assessing potential risks and threats, and promoting mechanisms to prevent statecraft maneuvers (e.g., access to sensitive data and manipulation).

• Regarding the international community, it is faced with a new reality shaped by cyberspace, with China appearing to lead, so it must respond by promoting global governance instruments that ensure the proper management of transnational digital infrastructure and protect the interests of all states.

• The West, in light of China’s advancements in the digital sector, appears to be falling behind, and in response, should promote alternative opportunities to DSR, particularly through the Build Back Better World and Global Gateway initiatives.

Sino-Brazilian relations, restoring synergies that had been suspended during the previous administration.

This paper draws on a qualitative methodology based both on secondary sources and primary sources. The latter include news agencies like Xinhua and China Daily; official documents from Chinese and Brazilian governments; reports from institutions and think tanks, like the Council on Foreign Relations and the Brazilian Center for International Relations. Additionally, we have elaborated and applied an online survey to measure the perceptions on the DSR security repercussions in Brazil. In order to achieve more reliable outcomes, we have decided to complement the survey with five pre-selected interviews conducted mostly with experts from Latin America.

This paper is divided as follows. The first section attempts to con- nect the dots between the DSR, Netpolitik, and Digitalpolitik. Next, once these concepts are introduced and explained, the subsequent sections will provide empirical evidence of elements of Digital politik linked to the DSR in the case of Brazil. The conclusion summarizes the main findings.

In alignment with recent think tank reports and the position of other international actors, such as the European Union, this study starts from the premise that the DSR does not necessarily reflect the win-win rhetoric associated with the BRI narrative, but rather represents a struggle for power and influence in the digital realm. Therefore, we argue that the liberal perspective (Netpolitik) is no longer sufficient to fully under- stand the new dynamics underlying states’ hybrid strategies. As such, this paper posits that the DSR is best understood through the concept of Digital politik. Here, we find an opportunity to contribute to the state of the art by addressing a gap in the existing literature, which has mainly emphasized the liberal use of the Internet (Cabestan 2020; Jiang and Fu 2018; Su et al. 2022), although neglecting its potential for monitoring human behavior. Besides, this work seeks to contribute to filling another gap, namely the Chinese strategy of digital influence in Brazil under the DSR. Thus, this paper aims to answer the following research question: How has the Digital Silk Road evolved in Brazil?

In an attempt to explore the dynamics around the DSR in Brazil, our study will focus on the period from 2015 to 2024. In fact, our analysis begins in 2015, when China launched DSR and when Chinese technology companies strengthened their pres- ence in the Brazilian market, and extends to the present day, 2024, taking into account the transition of government from Jair Bolsonaro to Lula da Silva, which brought a new dynamic to

2 | Connecting the Dots: Digital Silk Road, Netpolitik and Digitalpolitik

To examine the expansion and implications of the DSR in Brazil, it is essential to first understand the objectives and dimensions of this initiative. In this section, we will there- fore provide a brief overview of DSR, followed by the introduction of the conceptual lens we will use in our analysis: Digitalpolitik.

The first reference to a digital corridor emerged during the presentation of the BRI action plan in March 2015, which set the goal of creating an ‘Information Silk Road’ (Xinhua 2015a). The first official mention of the DSR came a few months later, in July 2015, at the China-EU Digital Cooperation Forum, associated with the Internet Plus plan, which intends to connect Chinese territory through super-fast broadband. Finally, in May 2017, Xi Jinping called for the establishment of a ‘21st Century Digital Silk Road’ aimed at “intensifying cooperation in frontier areas such as digital economy, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and quantum computing, and advanc- ing the development of big data, cloud computing, and smart cities” (Xinhua 2017b).

The DSR is positioned as a technological and digital infrastructure initiative capable of connecting all peoples considering the above mentioned realms (Chung 2023; Hussain et al. 2024). In this way, China proposes to assist “other countries in building digital infrastructure, constructing transnational platforms for e-commerce, generation of QR codes, export promotion, financial transactions, and developing mechanisms of internal secu- rity surveillance” (Chung 2023, 124–25). Additionally, Beijing has invested in the development of a digital currency in an at- tempt to counter the dominance of the dollar in e-commerce (Aysan and Kayani 2022). Thus, the DSR clearly encompasses geoeconomic elements, along with geopolitical and geostrategic dimensions related to the control of critical digital infrastruc- tures (Chung 2023; Hussain et al. 2024; Shen 2018).

Traditionally, the DSR has been analyzed as a seemingly be- nign and positive initiative for global trade. This view is as- sociated with the liberal perspective on digital networks, Netpolitik. According to Bollier (2003, 2), Netpolitik describes as “a new style of diplomacy that seeks to exploit the powerful capabilities of the Internet to shape politics, culture, values, and personal identity.” Although the term suggests a connec- tion to realpolitik, Netpolitik is distinct from this classical form of doing politics and diplomacy. Instead of coercion and amorality, Netpolitik focuses on “softer” issues such as social values and cultural identity, aligning with the liberal per- spective of International Relations. Netpolitik posits that the Internet has enabled a liberalization and democratization of international politics, allowing other actors, notably civil so- ciety, to participate in and influence this arena. Consequently, non-state actors have acquired new capacities to impact po- litical processes, thereby enabling them, alongside states, to wield soft power (Bollier 2003; Maniscalco 2006).

However, throughout this paper, we challenge the application of this liberal perspective to the DSR, arguing that China uses the initiative as an instrument of power. This stance aligns with the findings and arguments of various think tank reports and the position of several international actors, notably the European Union. In this regard, it is important to revisit the European Parliament Resolution of March 12, 2019, which highlights the risks associated with Chinese investment and digital presence in Europe, particularly due to China’s national security legislation, which requires companies to cooperate with authorities on matters of security and cyberse- curity (European Parliament 2019). Similarly, a report by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation noted that “as an aspiring global hegemon, China uses a combina- tion of carrots and sticks to bribe and bully other nations into submission, including its ‘digital silk road’” (Atkinson 2021). Indeed, it is through this report that Digitalpolitik is intro- duced as an approach for states to shape their digital policies and utilize digital networks as instruments of power. Based on the assumptions outlined in this document, we can formulate a theoretical framework for Digitalpolitik.

Like Realpolitik and Netpolitik, Digitalpolitik is more than a mere theoretical framework; it constitutes a method of political action and diplomacy. From the perspective of Digitalpolitik, states should prioritize technological and digital development, ensure control over domestic data and digital infrastruc- tures—thereby safeguarding their digital sovereignty—pro- mote digital free trade, and seek to limit the technological advancements of adversaries (Atkinson 2021). In doing so, the main objective is to secure global leadership in the technolog- ical domain (ibid.).

Thus, in contrast to Netpolitik, which is founded on international cooperation, free trade, civil society participation, cultural and geographical proximity, and respect for freedom, privacy, and data protection, Digitalpolitik prioritizes technological competi- tion and the use of digital networks as instruments of power and political influence (Atkinson 2021; Bollier 2003).

Furthermore, according to Digitalpolitik, digital networks serve as a means for states to secure control over data and

digital infrastructures, shape narratives, disseminate disinfor- mation, attack critical infrastructures, and conduct espionage (Atkinson 2021). Consequently, Digitalpolitik is premised on the notion that the logic of the international system is one of tech- nological competition, wherein each state must strive to achieve leadership not only by developing more advanced technologies than its adversaries but also by curbing their technological prog- ress (ibid.).

Digitalpolitik entails the use of digital networks and means as instruments of national interest, enabling states to assert power and reshape international structures in their favor, rather than fostering cooperation. Central to this approach is the concept of digital sovereignty, a concept that has recently emerged as an adaptation of the traditional Westphalian notion of sovereignty.

In its traditional and Westphalian form, sovereignty is under- stood as the supreme authority and exclusive competence to make decisions within a political-territorial entity, as well as external independence from other states (Evans and Neumham 1998). Recent technological advancements and the rise of digital tech- nologies, particularly the internet, have challenged this tradi- tional conception (Pohle and Thiel 2020). Phenomena such as the growing ability of digital platforms to influence trade and communication, along with state-led mass surveillance prac- tices, have challenged sovereignty by circumventing traditional state structures (Hulkó et al. 2025; Pohle and Thiel 2020). As a response to the challenges posed by digitalization, digital sov- ereignty has emerged, requiring states (or other entities) to en- sure an orderly, regulated, and secure digital sphere (Falkner et al. 2024; Pohle and Thiel 2020). This includes elements such as controlling dependencies, managing digital data, develop- ing and maintaining technological and digital infrastructure, protecting digital infrastructures from cyberattacks, and estab- lishing and enforcing a legal framework in cyberspace (Falkner et al. 2024; Hulkó et al. 2025; Pohle and Thiel 2020). In short, digital sovereignty refers to the ability to ensure independence and control over digital infrastructures, technologies, and data (Couture and Toupin 2019).

Thus, considering that China has developed a digital connec- tivity strategy through the DSR, which involves censorship, control, and surveillance, we argue that the Netpolitik frame- work is inadequate for analyzing this strategy. Instead, we pro- pose interpreting the DSR through the lens of Digitalpolitik. Table 1 provides an overview of the differences between these two approaches, facilitating the operationalisation of variables throughout our study

3 | Integrating Latin America Into the Digital Silk Road

In this section we will explore DSR dynamics within Latin America. Given that our study focuses on analyzing the expan- sion and implications of the DSR in Brazil, it is crucial to first provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of this project in the broader regional context.

TABLE 1 | Netpolitik vs Digitalpolitik: tenets and view on the DSR.

Aspects and tenets Liberal approach—Netpolitik Realist approach Digital politik

Logic of the International System Cooperation Competition

View on Digital Networks Fostering liberalization, free trade,

cooperation and development

Instrument of power and political influence

Objectives Democratization of international politics Technological and digital dominance and digital sovereignty

Actors Civil Society State

View on Sovereignty Globalization Digital sovereignty

Freedom vs. Security Freedom Security State Interests vs. Citizens’ Rights Protection of Individual Rights State Interests

Interpretation of the Digital Silk Road Tool for global cooperation

and connectivity

Tool for acquiring power and influence

Source: The authors based on Bollier (2003) and Atkinson (2021).

Initially, the BRI did not encompass Latin America. In fact, Xi Jinping’s speeches and the Chinese government’s documentrelated to the BRI, such as the 2015 Action Plan, initially re- ferred to the initiative as an infrastructure project aimed at connecting Asia, Europe, and Africa (Xinhua 2015a). The ex- pansion of the BRI to Latin America occurred with the Second Ministerial Meeting of the China-CELAC Forum in January 2018, where Latin American countries expressed receptiveness to the opportunities arising from this project (Xinhua 2018). Since then, 22 Latin American countries have signed Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with China regarding the BRI, with five of these countries signing agreements related to the DSR (Arsentyeva 2024; Green Finance and Development Center 2023).

The expansion of the BRI into Latin America reflects a gradual rapprochement between Beijing and the region (Jenkins 2017; Li 2007). As a main motivation, we can identify, on one hand, China’s increasing geopolitical and geo-economic interest in Latin America, and on the other hand, the Latin American countries’ need to find solutions to development challenges in a region only surpassed by Africa in terms of underdevelopment (Ferreira Abrão 2023; Arsentyeva 2024; de Sousa et al. 2023).

China’s deep economic ties with Latin America are evident, as it is the region’s second-largest trading partner after the US, a role it has maintained both before and during the BRI era (Roy 2023; Zhang and Prazeres 2021). Despite the US remaining the pri- mary trading partner of Latin America, China has seen its trade with the region increase, while the US has experienced a de- cline, particularly since 2018 (Roy 2023). Specifically in South America, China has already surpassed the US as the largest eco- nomic partner (ibid.). For instance, in 2021, according to data from the World Integrated Trade Solution1, trade between Latin America and China totaled over US$ 400 billion, representing an increase of nearly 4000% compared to the year 2000. In contrast, trade with the US amounted to approximately US$ 860 billion, an increase of about 220% from 2000. Data from 2020 indicate that the countries where trade with China constitutes a signif- icant portion of total trade are Chile (34%), Brazil (28%), and Peru (28%) (Roy 2023). Regarding Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), a report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean concluded that this was quite

limited until 2010, the year when several Chinese companies from various sectors, such as energy and mining, arrived in the region (Chen and Ludeña 2024). According to Statista2 (2023), in 2022, the total Chinese foreign direct investments in Latin America reached nearly US$ 600 billion, marking an increase of almost 900% compared to 2012.

China’s attention to Latin America has led to the gradual inclu- sion of this region in Chinese strategy, with references made in several policy papers, such as The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future (2023), China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System in the New Era (2022), Fighting Covid-19: China in Action (2020), and China and the World in the New Era (2019) (Ferreira Abrão 2023; Arsentyeva 2024). The China-CELAC cooperation plan for the biennium 2022–2024 outlines various areas for cooperation, placing particular emphasis on the digital realm, including trade, industry, security, and infrastructure, with a special focus on 5G, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and smart cities (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2021).

Within the scope of the BRI, the main areas of financing have been railway, port, road, and airport infrastructures, as well as electric and digital connectivity infrastructures, with a special emphasis on 5G (de Sousa et al. 2023). In this regard, we ob- serve the introduction of Chinese technology sector companies in Latin America, with special emphasis on Huawei and ZTE, which are involved in projects to expand and modernize tele- communications, primarily linked to 5G (Arsentyeva 2024; de Sousa et al. 2023).

The DSR arrives in Latin America not only through 5G, but also through surveillance and citizen control technologies and systems (E. Ellis 2021). Given the high crime rates in Latin American cities, the security concerns of governments in this region have led to the search for surveillance solu- tions. Consequently, several Latin American countries, such as Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay, and Bolivia, have turned to Chinese companies in search of smart and safe city solutions. In this domain, noteworthy instances include the installa- tion of the ECU 911 n.d. surveillance system3 in Ecuador by

Huawei and the China National Electronics Import & Export Corporation, which began development in 2011; the supply of surveillance cameras to Argentina by ZTE in 2019; the secu- rity system developed by ZTE in Bolivia (BOL-1104) using fa- cial recognition tools; and the surveillance system, composed of a thousand cameras, installed in Uruguay along the border with Brazil (Infodefensa.com 2019; Reuters 2019; The New York Times 2019; Xinhua 2019). Such evidence shows that the appli- cation of digital means in the framework of the DRS goes be- yond the realm of trade (Netpolitik) to fulfill the security needs of states, thus featuring in the Digitalpolitik domain.

On the other hand, the DSR has also materialized in Latin America through digital connectivity projects via submarine fiber optic cables. In this regard, and according to data provided by the ‘Reconnecting Asia’ platform of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, there is a comprehensive coverage of Hikvision cameras across several Latin American countries, such as Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, among others (Reconnecting Asia 2021). In terms of submarine cables, Huawei Marine installed the Fibra Optica al Pacífico, con- necting Ilo to Lurín in Peru, and the Fibra Optica Austral cable, connecting various Chilean localities, namely Puerto Montt, Puerto Williams, Punta Arenas, and Tortel (Reconnecting Asia 2021; TeleGeography 2024). Latin American countries seek high-quality equipment at reduced prices, and China, through the DSR, offers them an opportunity to develop, particularly by providing a range of financial instruments much cheaper than those provided by the West (Arsentyeva 2024).

Despite the advances of the BRI and the DSR in Latin America, there are still several challenges and obstacles that hinder greater involvement of this region in both Chinese initiatives. This is the case of the absence of MoUs with several Latin American countries; the ties of many Latin American states to Taiwan; and the influence of the US, which views Latin America as its ‘backyard,’ as stated by Kissinger (Ferreira Abrão 2023; de Sousa et al. 2023). Also, some of the largest economies are absent from the BRI, although they cooperate with China and participate in BRI fora and institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Brazil, however, is an atypical case. Although it is not formally part of the initiative, Sino-Brazilian cooper- ation is as deep, if not deeper, than the cooperation between China and its BRI partners. In fact, in April 2023, Brazil signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on cooperation in the digital economy, thereby becoming part of the DSR, a dynamic that we will further explore in the next section.

4 | Unpacking the Digital Silk Road in Brazil

Having introduced our conceptual framework and contextual- ized our case study within the regional landscape by examining the evolution and current state of the DSR in Latin America, we will now address the specific case of Brazil. This section is divided into two subsections. The first will frame the Brazil- China relationship, including the transition from the Bolsonaro administration to the Lula administration, which we consider a turning point in the bilateral relations, namely regarding the will to embrace China’s economic opportunities. Based on this more overt stance, the second subsection will focus specifically

on the implementation and repercussions of the DSR in Brazil, analyzing how this initiative is influencing Brazil’s digital infra- structure and security dynamics.

4.1 | Framing Brazil-China Relations

The China-Brazil relationship dates back to the 1970s, with nota- ble milestones including the signing of the Strategic Partnership Agreement in 1993, which was the first of its kind for China; the establishment of the Brazil-China High-Level Commission for Coordination and Cooperation in 2004; the evolution of the relationship to a Global Strategic Partnership; and the creation of the Global Strategic Dialog in 2012 (Ministério das Relações Exteriores 2024). This comprehensive partnership transcends bilateral ties, engaging multilateral platforms like BRICS, the China-CELAC Forum, and the Forum Macao.

Despite Brazil not being formally part of the BRI, as it has not signed a MoU regarding the initiative, cooperation between Beijing and Brasília has been one of China’s strategic priorities (Dreyer 2019; de Sousa et al. 2023). Indeed, Brazil’s cooperation with China exceeds the scope of many states that are formally part of the BRI, such as Argentina or Uruguay. Moreover, since 2009, China has been Brazil’s main trading partner, with Brazil not only being one of the top recipients of Chinese investment, but also the first Latin American country to achieve a trade vol- ume with China of US$ 100 billion (Xinhua 2023; Reuters 2023). For instance, at the beginning of 2024, Brazil’s exports to China increased by approximately 53.7%, reaching a total of US$ 7.769 billion, while imports of Chinese products rose by 10.2%, amounting to US$ 5.062 billion (Comex 2024). Furthermore, un- like the common practice of the BRI, the expansion of the DSR does not always appear to require the signing of MoUs, although such agreements do exist (Arsentyeva 2024).

Perhaps, one of the most significant challenges to Sino-Brazilian relations was the administration of Jair Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro’s ideological alignment with then-US President Donald Trump prompted him to adopt a critical rhetoric towards China, view- ing it as a threat. Nonetheless, despite limited formal progress in relations during his tenure, trade relations between Brazil and China continued to thrive (Cariello 2021; UOL Notícias 2022). In January 2023, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva returned to the Palácio do Planalto, thus succeeding Jair Bolsonaro. Lula’s pre- vious administrations (2003–2007 and 2007–2011) had been characterized by a focus on enhancing partnerships within the Global South and significantly expanding relations with China (Oliveira 2010). There was a widespread expectation that Lula’s new administration would similarly prioritize strengthening ties with China, and this expectation was promptly fulfilled.

In April 2023, Lula visited Beijing, returning with a firm be- lief that Sino-Brazilian relations would advance to new levels, encompassing areas such as connectivity, culture, and com- modities (Presidência da República 2023). During the visit, various MoUs were signed between Brazilian and Chinese companies, as well as between the Brazilian government and Chinese firms, with a key highlight being the agreement for Banco BOCOM BBM to join the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System, China’s alternative to the SWIFT system

(Ministério das Relações Exteriores 2023). In July 2024, Lula reaffirmed his intention to strengthen ties with China, partic- ularly in technological sectors, while maintaining a balanced relationship with the US (Globo G1 2024). In the same month, Lula announced that Brazil was preparing an official request to join the BRI (Estadão 2024). Despite concerns from some political sectors that formal accession to the BRI could jeop- ardize Brazil’s relationships with Western countries, the Lula administration appears confident in the benefits of joining this initiative, reiterating its interest in deepening relations with China (ibid.).

4.2 | The DSR Footprint in Brazil

As previously noted, the absence of a MoU between China and Brazil has not hindered the deepening of commercial and investment relations between the two countries, allowing us to characterize Brazil as an informal partner of the BRI. Significant advancements have been observed not only in the cooperation between both states, but also in the partnerships between Brazilian and Chinese companies, including in the dig- ital realm. As highlighted by Malena (2021), Brazil is one of the few Latin American countries that has systematically invested in digital infrastructure and services, making it particularly at- tractive to Beijing.

In 2018, Brazil’s Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations, and Communications launched a digital strategy known as the Brazilian Strategy for Digital Transformation, or simply E-Digital. This strategic action plan, revised in 2022, aims to harness digital technologies for Brazil’s economic and social de- velopment. It focuses on key areas such as Artificial Intelligence, the Internet of Things, Big Data, cloud computing, mobile sys- tems, cybersecurity, and quantum computing (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovações 2022). While Brazil’s increasing focus on digital technologies presents an opportunity for China to expand the DSR into the country, it is also true that Chinese investment, and by extension the DSR itself, can be viewed as tools to address Brasília’s digital and technological needs. In this context, in April 2023, China and Brazil signed a ‘Memorandum of Understanding on Strengthening Cooperation in Investments in the Digital Economy’ (Federative Republic of Brazil and People’s Republic of China 2023). This MoU underscores the growing importance of the digital sector and, consequently, digital cooperation between the two countries. It highlight pri- ority areas of cooperation such as the development of communi- cation infrastructures like broadband and satellite navigation, cloud computing and data processing (Big Data) infrastructures, and smart infrastructures encompassing Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, 5G, and smart cities (ibid.). The MoU also includes provisions for cooperation aimed at harmonizing reg- ulations and standards related to the digital economy, as well as the adoption of digital and intelligent payment systems (ibid.). Additionally, it stipulates that both parts will collaborate on training and capacity building in digital skills, alongside inno- vation and research in digital technologies (ibid.). This approach is consistent with China’s common practice under the DSR, in which investments are provided to develop the digital sector of partner states. In return, Beijing gains access to new markets for its companies, expands its influence, and sets new standards, gradually challenging US hegemony, an expectable behavior ac- cording to the Digitalpolitik which sees digital means as comple- mentary tools to help states maximize their goals.

This was the first major MoU signed between China and Brazil in relation to the digital sector. It was followed by the signing, throughout 2024, of new MoUs related to the digital domain. The first noteworthy MoU was signed on 20 August for the reinstate- ment of the Cooperation Fund for the Expansion of Productive Capacity for Sustainable Development, a fund initially estab- lished in 2017 but deactivated under Bolsonaro’s administration (Tele.Síntese 2024). This fund allocates R$ 7.6 billion (approxi- mately €1.2 thousand million), provided by China, primarily for investments in the green economy, as well as in digital infra- structures (ibid.).

Subsequently, in November of the same year, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Brasília, 37 new agreements were signed, including new MoUs in the digital sector (O Globo 2024; Brazilian Ministry of Communications 2024). Notably, in the field of artificial in- telligence, the ‘Memorandum of Understanding for Enhancing Cooperation in Artificial Intelligence Capacity Building’ and the ‘Memorandum of Understanding on the Establishment of a Joint Laboratory for Mechanization and Artificial Intelligence for Family Agriculture’ stand out (ibid.). Another significant MoU involves Telebras, Brazil’s state-owned telecommunica- tions company, and SpaceSail, a Chinese company developing an internet service through a low Earth orbit satellite system, which competes with Elon Musk’s Starlink (ibid.). Additionally, there is an MoU between Brazil’s Ministry of Communications and China’s National Data Administration for the development of digital infrastructure (ibid.).

The expansion of the DSR into Brazil includes digital con- nectivity infrastructures related to 5G, satellite navigation, Artificial Intelligence, and Big Data, as well as oceanic con- nectivity infrastructures, such as submarine fiber optic cables, digital banking, and the space sector. In terms of connectivity infrastructure, Huawei’s participation in the Brazilian market is particularly notable. Currently, Huawei is the leader in Latin America for the installation of 5G network infrastructure (R. E. Ellis 2023). In Brazil, Huawei entered the market in 1996 and became the largest supplier of mobile network technolo- gies in 2014 (Xinhua 2015b). The company collaborates with various Brazilian institutions, having established joint labora- tories with the University of São Paulo and the University of Brasília, as well as an agreement with the National Institute of Communications to create a ‘network technology college,’ and a research and training center in Campinas (ibid.). Despite the initial anti-China stance of the Bolsonaro administration, Brazil authorized Huawei to participate in the development of the 5G network in 2021, at a time when China had provided millions of COVID-19 CoronaVac vaccines (Law 2023). In 2022, Huawei signed a MoU with the Brazilian operator TIM to create the first ‘5G City’ in Brazil, in Curitiba (Huawei 2022). This agreement involves implementing 5G network coverage across the entire city and services designed to reduce energy consumption and costs (ibid.).

Huawei’s presence, however, extends beyond terrestrial infra- structures. In fact, in 2017, Chinese companies China Unicom and Huawei Marine Networks announced plans to build a sub- marine fiber optic cable between Latin America and Europe, connecting Brazil to Portugal via Cape Verde (Malena 2021). At the same time, China Unicom, Huawei Marine Networks, and the Cameroonian company CamTel revealed plans to develop a submarine cable connecting Kribi Deep Sea Port in Cameroon to Fortaleza, Brazil (CCTV 2017; Huawei 2018b). Of the US$ 136 million cost, the Export–Import Bank of China financed US$ 85 million, with the remainder covered by CamTel and China Unicom (CCTV 2017). However, it appears that Huawei fell be- hind in the first project, with the Irish company EllaLink inau- gurating, in June 2021, the first high-capacity fiber optic cable between Latin America and Europe (Globo G1 2021). This cable, financed by the European Investment Bank and developed by the European company Alcatel Submarine Networks (Nokia), connects Fortaleza (Brazil) to Sines (Portugal) (Globo G1 2021; Teletime 2021). As for the second project, known as SAIL (South Atlantic Inter Link), it was completed in 2018, establishing a connection between Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa through Brazil and Cameroon (Tele.Síntese 2018).

Besides, Huawei has been active in public security projects in Brazil, in which other Chinese companies such as Hikvision and Dahua are also involved. Security is actually one import- ant tenet of the Digitalpolitik, which claims that states use comprehensive and dual strategies to protect their interests. Given Brazil’s high crime rates and widespread sense of in- security, the development of new surveillance initiatives has been deemed necessary. During Jair Bolsonaro’s administra- tion, Brasília implemented a strategy to strengthen the power of security forces, which included the creation of a database with personal and biometric information of Brazilian citizens, followed by the adoption of video surveillance and facial rec- ognition systems (Agência Brasil 2021). Concerned about se- curity, several senators from Bolsonaro’s party (Partido Social Liberal) were invited to visit China to closely examine sur- veillance technologies (Paulo 2019). In 2019, the city of Foz do Iguaçu started using Hikvision cameras for monitoring vehicle license plates. Besides, in 2020, the Brazilian federal government, supported by the Brazilian Agency for Industrial Development and the state government of Roraima, launched the Fronteira Tech project, employing Hikvision’s facial rec- ognition technology to oversee the border with Venezuela (Hikvision 2022).

Moreover, in 2021, the city of Rondônia acquired police ve- hicles equipped with security cameras and facial recognition systems using Dahua technology (Ferreira 2021). Additionally, Huawei has sought to expand its footprint in Brazil by donat- ing surveillance systems to the cities of Campinas, Mogi das Cruzes, and São Paulo (Majerowicz and Carvalho 2024). In 2018, Huawei initiated a project in Campinas to develop a ‘safe city,’ aiming to transform the city into a ‘living lab’ for security solutions, including smart camera monitoring, LTE broadband installation, E-Police and HD Checkpoint solu- tions, Big Data policing through surveillance data analysis on Huawei’s platform, and cloud services for data hosting (Huawei 2018a; Ionova 2020). Moreover, the project involves creating a Telecommunications Research and Development Center focused on information and communication tech- nologies applied to security (Huawei 2018a). That same year, the Brazilian telecommunications company Oi, in col- laboration with Huawei, introduced a ‘safe and smart city’ solution incorporating digital surveillance systems for mon- itoring, facial recognition, and vehicle license plate recogni- tion (Teletime 2018).

Huawei’s presence is also notable in the realm of data centers, with cloud storage facilities in Brazil, particularly in São Paulo (R. E. Ellis 2023). These data centers provide services support- ing corporate communications and processes, as well as health- care (ibid.). Additionally, Tencent operates data centers in Brazil that support the operations of its affiliate company, Alibaba. According to Ellis (2023), these data centers enable Chinese companies to influence, or even compel, Brazilian vendors and consumers to provide sensitive data on platforms accessible to these firms. Here, Chinese companies are clearly crossing the red line that separates the Netpolitik liberal view of communi- cations and entering the use of information and technology that states seek to control according to Digitalpolitik.

Finally, it is also important to highlight notable advancements in other areas, such as the rapid rise of AliExpress, Alibaba’s in- ternational arm, which entered Brazil in 2014 and has since be- come one of the country’s leading digital commerce platforms; and the investment by the Chinese company Tencent, affiliated with WeChat, in NuBank, a pioneering Brazilian firm in the dig- ital banking sector (Malena 2021; Reuters 2018).

In recent years, we have observed a significant increase in Chinese investment in the Brazilian digital sector, encompass- ing various areas of the DSR. In this context, the signing of the MoU on digital economy cooperation should be seen as a milestone in Brazil-China digital cooperation, representing the first major agreement formalized between the two states in this area. This was followed by the signing of additional MoUs in the digital sector, further expanding the scope of cooperation and opening new avenues for digital collaboration between the two countries and increased Chinese digital investment in Brazil. Based on this, we argue that the signing of this MoU formalizes and symbolizes Brazil’s accession, or at the very least, its partic- ipation in the DSR5.

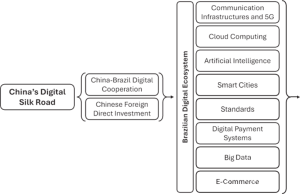

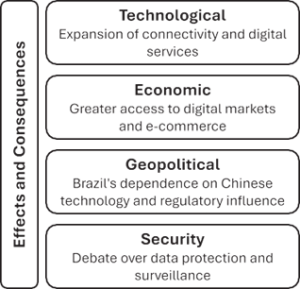

By engaging in agreements in key sectors such as artificial intel- ligence, telecommunications, and digital infrastructure, Brazil not only demonstrates its involvement in this project but also aligns itself with China’s strategic objectives in these domains. This dynamic manifests, as shown in Figure 1, through tech- nological effects related to the expansion of digital services in Brazil; economic impacts, enabling access to digital markets; geopolitical implications, highlighting the risk of dependency on China and the growing influence, even control, of China over Brazil; and security concerns, associated with the risks of espio- nage and surveillance.

5 | Brazilian Perceptions of the DSR

FIGURE 1 | Multidimensional Effects of the DSR in Brazil. Source: The authors.

The objective of this section is to present and interpret perceptions surrounding the DSR in Brazil. In doing so, we aim to better assess how the DSR has evolved in Brazil. Thus, in this section, we will present the perceptions of Brazilian society in general, the perceptions of academics, and the perceptions of Brazilian policymakers. Through this, we seek to understand the Brazilian view of the DSR and how it has influenced its ex- pansion in Brazil.

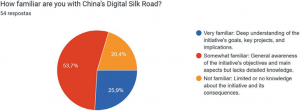

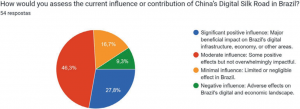

To achieve this, we first developed an online survey consisting of three questions (annex 1). The first question aimed to under- stand the respondents’ (1) familiarity with China’s DSR, while the remaining questions focused on (2) the current influence and contribution of China’s DSR in Brazil, and the (3) security risks regarding the DSR in Brazil.

The survey was distributed to three distinct groups: (1) research- ers focusing on Brazil’s involvement in the BRI, (2) Brazilian researchers studying Brazil-China relations, and (3) Brazilian citizens. This approach aims to gather expert insights from both Brazilian and international researchers, as well as the percep- tions of the general public, including those less informed about Brazil’s participation in the BRI.

Additionally, we sought expert perspectives by reaching out to specific groups of scholars and policymakers specialized in Chinese affairs. These included: (1) Working Group 1 of the China in Europe Relations Network (CHERN) COST Action;

(2) the China-Eurasia WeChat Group6; (3) members of the Portuguese think tank New Silk Road Friends Association;

(4) members of the China Observatory; (5) the Portugal-China Friendship League; and (6) Lusoglobe, totaling approximately 320 individuals.

Among the study’s limitations, the lack of specialists exclusively dedicated to the DSR stands out, as it remains a relatively recent corridor with less attention compared to the SREB and MSR. Furthermore, results relying on less informed citizens may not be entirely reliable. However, the intention was to combine ex- pert insights with the general public’s perceptions to avoid frag- mented conclusions that might overlook either the academic sector or the broader public’s views.

At the same time, we sought to identify academics’ perceptions of the DSR. To achieve this, we conducted semi-structured inter- views, which were sent to a selection of academics specializing in the topic. The insights gained will enable us to better under- stand the general perception of the DSR in Brazil, particularly when discussed alongside the perceptions of the general public and policymakers.

Through the online survey conducted, we received 54 responses (Annex 2). Of these, 53.7% came from respondents with a deep understanding of the DSR’s goals, key projects, and implica- tions. Meanwhile, 25.9% were from respondents with a general awareness of the initiative’s objectives and main aspects, though lacking detailed knowledge, and 20.4% had limited or no knowl- edge about the initiative and its consequences, as illustrated in Chart 1.

When asked about the current influence and contribution of China’s DSR in Brazil, the majority of our respondents (46.3%) voted for ‘moderate influence,’ meaning that there are some positive effects although not overwhelmingly impactful; while 27.8% believe that there is a significant positive influence (in other words, the DSR has major beneficial effects on Brazil’s digital infrastructure, economy, or other areas). In turn, 16.7% of respondents consider that the DSR has only a minimal influ- ence, which is a limited or negligible effect in Brazil. A smaller percentage, composed of 9.3% of respondents claim that the DSR has a negative influence which translates into adverse effects on Brazil’s digital and economic landscape, as Chart 2 indicates.

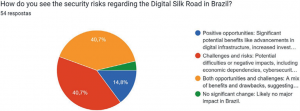

Finally, when asked about the security risks of the DSR in Brazil, respondents were evenly split (40.7% each) between two perspectives: One highlighting “challenges and risks,” such as economic dependencies, cybersecurity threats, or geopolitical tensions, and the other emphasizing “both opportunities and challenges,” reflecting a nuanced view of benefits and draw- backs. Expert opinions support this division. Adrian Kadriu7 highlights risks like espionage and sabotage tied to Chinese

CHART 1 | Respondents’ familiarity with the Digital Silk Road. Source: Survey data collected by the authors.

CHART 2 | Perceptions on the Digital Silk Road’s Influence in Brazil. Source: Survey data collected by the authors.

Finally, when asked about the security risks of the DSR in Brazil, respondents were evenly split (40.7% each) between two perspectives: One highlighting “challenges and risks,” such as economic dependencies, cybersecurity threats, or geopolitical tensions, and the other emphasizing “both opportunities and challenges,” reflecting a nuanced view of benefits and draw- backs. Expert opinions support this division. Adrian Kadriu7 highlights risks like espionage and sabotage tied to Chineseinvestments in Brazil’s digital sector (Interview, July 31, 2024), a concern shared by scholar Sabrina Medeiros8, who identifies po- tential geopolitical risks from dependency but notes that robust legislation could mitigate these threats. She also views the DSR as a key opportunity for Brazil’s digital development (Interview, July 30, 2024). In fact, according to Kadriu,

Chinese technology, particularly in critical infrastructure like telecommunications, could be used for intelligence gathering, posing a direct threat to Brazil’s national security. Integrating Chinese technology into Brazil’s critical infrastructure, such as communication networks and public services, could create security vulnerabilities. In a geopolitical conflict, these systems might be susceptible to disruption or sabotage, compromising Brazil’s national security.(Interview, July 31, 2024)

Meanwhile, 14.8% of respondents perceived DSR as a source of “positive opportunities,” such as advancements in digital infra- structure, increased investment, or improved trade relations. This position is shared by some experts, such as Javier Vadell9, who argues that Chinese technology does not pose a threat to Brazil’s security. In fact, he considers the DSR as ‘the best op- portunity’ for Brazil to advance its digital ecosystem (Interview, July 30, 2024). Likewise, Brazilian scholar Diego Pautasso10 maintains that the idea of Chinese technology as a threat is “nothing more than ethnocentrism,” and asserts that Brazil can rely more on Chinese investment than on American investment

(Interview, July 29, 2024). Similarly, Giorgio Romano11 argues that Chinese tech supports Brazil’s digital sovereignty rather than threatening it (Interview, July 30, 2024). Lastly, 3.7% of re- spondents felt the DSR had not brought significant changes to Brazil, as shown in Chart 3.

Overall, the data obtained from our survey demonstrate a clear perception of a significant or moderate effect of the DSR in Brazil. Regarding the repercussions, however, we highlight a division among respondents, revealing a contrasting per- ception between the benefits and risks associated with the initiative. Nevertheless, the collected data supports our view that the DSR is progressively extending into Brazil. While the full implications of this expansion may not yet be clear, the experience suggests that establishing new dependency net- works with China, along with China’s access to critical infra- structure and sensitive data, could pose future challenges for Brazil. In this context, it is pertinent to recall Adrian Kadriu’s view, which holds that the control of critical infrastructure and access to sensitive data by Chinese companies could ren- der Brazil vulnerable to geopolitical pressures from China (Interview, July 31, 2024).

The perceptions of Brazilian policymakers regarding the DSR are difficult to access. However, they can be inferred from the perceptions of Brazilian policymakers concerning the BRI, digital sovereignty, and Chinese investment in the digital sec- tor. In this regard, it is worth referencing a recent study by Ferreira Abrão and Amineh (2024), which involved officials, diplomats, and Brazilian politicians.

CHART 3 | Perceptions on the Security Risks brought by the DSR in Brazil. Source: Survey data collected by the authors.

The study concluded that Brazil’s non-participation in the BRI is justified by the percep- tion that joining would not bring significant commercial bene- fits, as substantial Chinese investments already exist in Brazil, even without formal participation in the initiative. This view is also supported by Maurício Santoro, who recognizes that, for the Itamaraty, there would be no considerable gains from joining (BBC Brasil 2024). The study by Ferreira Abrão and Amineh (2024) also highlights that Brazil’s lack of formal par- ticipation in the BRI has not hindered the existence of Chinese investments in Brazil’s digital sector, further noting that, among Brazilian policymakers, China’s growth and Chinese invest- ment are not seen as a threat.

Brazilian policymakers’ perception of Chinese investment has shifted with the recent change in administration, as we have previously noted. During the Bolsonaro administration, an ini- tially critical and skeptical stance towards Beijing was adopted, but the administration eventually adjusted its position (Rubiolo and Fiore 2024). In fact, Bolsonaro went so far as to identify China as Brazil’s “great commercial partner” (Estadão 2019), and members of his then party, the PSL, even visited China to explore surveillance systems offered by Chinese companies (Paulo 2019).

Under Lula, the perception of China improved considerably. This is evident in the signing of the agreements and MoUs al- ready mentioned. In November 2024, Lula stated that he was confident that the partnerships established between China and Brazil would “exceed all expectations,” emphasizing that the future of cooperation would focus on areas such as the digital economy and artificial intelligence (UOL 2024). The Brazilian Minister of Communications, Juscelino Filho, stated on the same occasion his interest in “elevating the bilateral relationship to a new level,” with a focus on digital cooperation (Brazilian Ministry of Communications 2024). However, this stance is not without dissent. For example, in March 2023, a federal deputy from the Liberal Party, the current party of Jair Bolsonaro, con- sidered Huawei’s participation in Brazil to be a “risk to national sovereignty” (A Referência 2023). Similarly, another federal dep- uty from the Liberal Party, Eduardo Bolsonaro, despite recog- nizing the BRI as a development opportunity, also highlighted that “this project also reflects the expansion of China’s global power and influence, which, due to its dictatorial political re- gime, exercises this influence more assertively” (Câmara dos Deputados 2024).

We observe a clear division not only among the survey respon- dents but also among experts and policymakers regarding the benefits and risks associated with the DSR. By interrelating these findings with the discussions in previous sections, it be- comes evident that, while the DSR offers significant advantages for Brazil’s economic development, it also poses certain risks to the country’s digital sovereignty. Nevertheless, within President Lula da Silva’s administration, perceptions appear to be predom- inantly positive, suggesting a potential strengthening of Brazil- China digital cooperation.

6 | Conclusion

Through this paper, we argued that the traditional liberal view of digital infrastructures as a tool for commerce and develop- ment, as defended by Netpolitik, is no longer adequate to in- terpret much of the states’ attempts to control information and behavior. Thus, this study sets itself apart from existing research by eschewing a cooperation-centric perspective that views digi- tal networks primarily as facilitators of trade. Instead, it adopts a more realist approach, foregrounding competition and the pri- macy of national interests. Rather than focusing solely on the benefits of digital networks, it critically examines their poten- tial adverse implications, particularly in relation to geopolitical and security risks. In doing so, it makes a novel and substantive contribution to the state of the art, while drawing policymakers’ attention to the inherent risks of digital engagement.

Building upon this premise, and in conjunction with the data col- lected, we arrive at three key findings. As a first major finding, despite not being a BRI formal partner, Brazil has nonetheless agreed to be part of China’s DSR. We have argued, and sought to substantiate throughout the text, that the increasing number of Brazilian digital projects funded by China, as well as the recent signing of several MoUs in the digital domain—most notably the MoU on cooperation in the digital economy—demonstrate this engagement. This move has entailed a significant expansion of China’s digital initiatives in the country, ranging from 5G, facial recognition, security cameras, smart cities solutions, fiber optic submarine cables, digital banking and digital payment solutions, Big Data, and research joint initiatives. Thus, the DSR appears to be emerging as a significant component of Sino-Brazilian coop- eration. The broad scope of projects receiving direct or indirect funding from the DSR, along with the growing number of MoUs signed between Brazil and China in the digital sector, serve as evidence of this.

Nevertheless, while such knowledge and cooperation can be seen as a boost to Brazil’s own digital ecosystem, as the interviews to the experts confirm, the DSR may also contribute to creating a negative situation in which Brazil becomes increasingly hostage to China’s appropriation of sensitive data. Here lies indeed our sec- ond major finding, also corroborated by the experts’ interviews. In order to mitigate the vulnerabilities arising from its dependence on China, Brazil should carefully navigate its involvement in the DSR by exploring alternatives, such as the European Union’s Global Gateway initiative and engagement with the US through the Build Back Better World project. This prudence and measured perspective on the DSR is supported by the data on public percep- tion gathered through our survey, as well as by the perceptions of experts and Brazilian policymakers, which indicate a division regarding the DSR’s implications for Brazil’s security.

However, as a third major finding, we should acknowledge that the relatively nascent stage of Chinese digital investments in Brazil constrains our ability to conduct a more comprehensive analysis on the DSR’s immediate consequences to the country. Thus, faced with the lack of substantial empirical evidence, which can only be overcome as the DSR matures with the test of time, we suggest that future academic works on this topic further seek to accompany the digital projects developed by Chinese companies in Brazil, considering that they are still in their early stages compared to other Latin American countries. Such avenues for research seem to be as or more promising since through the DSR, China acquires new tools for manipulation and coercion, whilst advancing its own norms (in opposition to the Western ones), thereby imposing new global standards in the digital ecosystems.

End notes

1 See https://wits.worldbank.org/countrysnapshot/en/LCN.

2 See https://www.statista.com/statistics/278017/capital-stock-in-chine se-direct-investments-in-latin-america/.

3 This surveillance system, consisting of thousands of cameras spread across the country, aims to reduce high crime rates by providing au- thorities with a monitoring tool that allows them to review past crime events (ECU 911 n.d.; The New York Times 2019).

4 This surveillance system aims to combat delinquency and provide an immediate response to crises and emergency scenarios, utilizing artifi- cial intelligence and facial and license plate recognition (Xinhua 2019).

5 In fact, the literature suggests that a country’s participation in the DSR does not necessarily hinge on the signing of a specific memoran- dum. Rather, most studies link DSR participation to the substantial volume of digital investments made by China in the country in ques- tion, alongside the signing of multiple MoUs within the digital sector, without a single memorandum explicitly formalizing membership.

6 Established by the help of VI edition of Eurasian Research on Modern China and Eurasia Conference. Approximately 95% of its members hold doctoral degrees in international relations, economics, while others are PhD students or practitioners.

7 Vice Dean of the Faculty of Political Science and Security at UBT College, Pristina, Kosovo, and specialist in National Security.

8 Professor at Universidade Lusófona and researcher at LusoGlobe— Lusófona Center on Global Challenges, Lisbon, Portugal.

9 Professor in the Department of International Relations at Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais and researcher at the Center for Global Studies and China, Brazil.

10 Professor at the Colégio Militar de Porto Alegre, Brazil.

11 Professor at the Federal University of ABC, Brazil.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to all participants who contributed to the survey, as well as to the experts who generously shared their in- sights during interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

Agência Brasil. 2021. Novo Sistema Da Polícia Federal Armazenará Dados Biométricos. Agência Brasil. https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/ geral/noticia/2021-07/novo-sistema-da-policia-federal-armazenara- dados-biometricos?amp.

Arsentyeva, I. I. 2024. “China’s Digital Silk Road: Challenges and Opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean.” Vestnik RUDN. International Relations 24, no. 1: 51–64. https://doi.org/10.22363/

Atkinson, R. D. 2021. A U.S. Grand Strategy for the Global Digital Economy. Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. https://itif.org/publi cations/2021/01/19/us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy/.

Aysan, A. F., and F. N. Kayani. 2022. “China’s Transition to a Digital

Currency Does It Threaten Dollarization?” Asia and the Global Economy

2, no. 1: 100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aglobe.2021.100023.

BBC Brasil. 2024. “Por Que Brasil Resiste a Entrar Em Nova Rota Da Seda Da China.” BBC News Brasil, November 20, 2024. https://www. bbc.com/portuguese/articles/cz7w2evgz5ro.

Bollier, D. 2003. The Rise of Netpolitik: How the Internet Is Changing International Politics and Diplomacy. Aspen Institute. https://www. bollier.org/rise-netpolitik-how-internet-changing-international-polit ics-and-diplomacy-2003.

Brazilian Ministry of Communications. 2024. Ministério Das Comunicações Assina Acordos Com a China Sobre Conectividade e Economia Digital. Brazilian Ministry of Communications. https:// www.gov.br/mcom/pt-br/noticias/2024/novembro/ministerio-das- comunicacoes-assina-acordos-com-a-china-sobre-conectividade-e- economia-digital.

Cabestan, J.-P. 2020. “The State and Digital Society in China: Big Brother Xi Is Watching You!” Issues & Studies 56, no. 01: 20400032. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1013251120400032.

Câmara dos Deputados. 2024. “Adesão Do Brasil à Nova Rota Da Seda Será Tratada Em Audiência Pública.” Câmara Dos Deputados, October 31, 2024. https://www2.camara.leg.br/atividade-legislativa/comissoes/ comissoes-permanentes/credn/noticias/adesao-do-brasil-a-nova-rota- da-seda-sera-tratada-em-audiencia-publica.

Caridi, G. 2023. China and Eurasian Powers in a Multipolar World Order

2.0. Routledge.

Cariello, T. 2021. Investimentos Chineses No Brasil: Histórico, Tendências e Desafios Globais (2007–2020). Conselho Empresarial Brasil-China.

https://www.cebc.org.br/2021/08/05/investimentos-chineses-no-brasi l-historico-tendencias-e-desafios-globais-2007-2020/.

CCTV. 2017. China Breakthroughs: SAIL à Frente Na Rede de Cabo Do Atlântico Sul. CCTV. http://english.cctv.com/2017/07/05/ARTITi0Qnt QhXqvZoN4dwobj170705.shtml.

Chang, Y.-C. 2018. “The ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative’ and Naval Diplomacy in China.” Ocean and Coastal Management 153, no. March: 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.12.015.

Chen, T., and M. P. Ludeña. 2024. Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean. United Nations Publication. https:// repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/35908.

China Daily. 2013. “Xi Proposes a ‘new Silk Road’ With Central Asia.” China Daily, September 8, 2013. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/ 2013xivisitcenterasia/2013-09/08/content_16952228.htm.

Chung, C.-p. 2023. “China’s Digital Silk Road.” East Asian Policy 15, no. 02: 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793930523000168.

Comex. 2024. “Comércio Brasil-China Inicia 2024 Com Fortes Altas Nas Exportações e Importações.” Comex Do Brasil (blog). February 14, 2024. https://comexdobrasil.com/comercio-brasil-china-inicia-2024- com-fortes-altas-nas-exportacoes-e-importacoes/.

Couture, S., and S. Toupin. 2019. “What Does the Notion of ‘Sovereignty’ Mean When Referring to the Digital?” New Media & Society 21, no. 10: 2305–2322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819865984.

Dave, B., and Y. Kobayashi. 2018. “China’s Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative in Central Asia: Economic and Security Implications.” Asia Europe Journal 16, no. 3: 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1030 8-018-0513-x.

de Sousa, A. T. L. M., G. R. Schutte, R. A. F. Abrão, and V. L. Ribeiro. 2023. “China in Latin America: To BRI or Not to BRI.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Globalization With Chinese Characteristics: The Case of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by P. A. B. Duarte, E. M. Galán, and F. J.

- S. Leandro, 495–514. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dreyer, J. T. 2019. The Belt, the Road, and Latin America. Foreign Policy Research Institute. (blog). January 16, 2019. https://www.fpri.org/artic le/2019/01/the-belt-the-road-and-latin-america/.

ECU 911. n.d. “Cámaras de Videovigilancia.” ECU 911. Accessed August 5, 2024. https://www.ecu911.gob.ec/camaras-de-videovigilancia/.

Ellis, E. 2021. “DiDi and the Risks of Expanding Chinese E-Commerce in Latin America.” Global Americans (blog). September 2, 2021. https:// globalamericans.org/didi-and-the-risks -of-expanding-chinese-e- commerce-in-latin-america/.

Ellis, R. E. 2023. “China’s Advance in Chile.” Diálogo Américas (Blog). December 13, 2023. https://dialogo-americas.com/articles/chinas- advance-in-chile/.

Estadão. 2019. “‘Nosso Grande Parceiro é a China, Em 2° Lugar Os EUA’, Diz Bolsonaro.” Estadão, March 14, 2019. https://www.estadao. com.br/economia/nosso-grande-parceiro-e-a-china-em-2-lugar-os- eua-diz-bolsonaro/.

Estadão. 2024. “Lula Fala Que Governo Elabora Proposta Para Adesão Do Brasil a ‘nova Rota Da Seda’ Da China.” Estadão, July 23, 2024. https://www.estadao.com.br/internacional/lula-fala-que-governo- elabora-proposta-para-adesao-do-brasil-a-nova-rota-da-seda-da-china/.

European Parliament. 2019. Security Threats Connected With the Rising Chinese Technological Presence in the EU and Possible Action on the EU Level to Reduce Them. Official Journal of the European Union. https:// www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2019-0156_EN.html.

Evans, G., and J. Neumham. 1998. The Penguin Dictionary of International Relations, 504–505. Penguin Books.

Falkner, G., S. Heidebrecht, A. Obendiek, and T. Seidl. 2024. “Digital Sovereignty – Rhetoric and Reality.” Journal of European Public Policy 31, no. 8: 2099–2120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2358984.

Federative Republic of Brazil and People’s Republic of China. 2023. “Memorando de Entendimento Sobre o Fortalecimento Da Cooperação Em Investimento Na Economia Digital Entre Brasil e China.” https:// www.gov.br/mdic/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2023/abril/memorando- economia-digital-final.docx/view.

Ferreira Abrão, R. A. 2023. “Belt and Road Initiative and China-Latin America Relations|A Iniciativa Cinturão e Rota e as Relações China– América Latina.” Mural Internacional 14, no. 1: 1–17. https://doi.org/10. 12957/rmi.2023.74301.

Ferreira Abrão, R. A., and M. P. Amineh. 2024. “Brazilian Perception of the China-Led Belt and Road Initiative.” Journal of Contemporary China 33, no. 150: 987–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2023.2299792.

Ferreira, F. 2021. Rondônia é o Primeiro Estado da América Latina a ad- otar tecnologias para implantação de IA, reconhecimento facial e placas em viaturas. Revista Segurança Eletrônica. https://issuu.com/revis tasegurancaeletronica/docs/revista_capa_ed50_issu.

Globo G1. 2021. “Entenda Como o Cabo Submarino Entre Brasil e Portugal Pode Mudar Sua Internet.” Globo G1, June 5, 2021. https://g1.globo.com/ economia/tecnologia/noticia/2021/06/05/entenda-como-o-cabo-subma rino-entre-brasil-e-portugal-pode-mudar-sua-internet.ghtml.

Globo G1. 2024. “Lula Exalta China e Diz Que Brasil Quer Fortalecer Relação Com o País, Sem ‘brigar’ Com Os EUA.” Globo G1, July 22, 2024. https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2024/07/22/lula-exalta- china-e-diz-que-brasil-quer-fortalecer-relacao-com-o-pais-sem-briga r-com-os-eua.ghtml.

Green Finance and Development Center. 2023. Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. https://greenfdc.org/countries-of-the-belt-and-road- initiative-bri/.

Halsall, J. P., I. G. Cook, M. Snowden, and R. Oberoi. 2023. “COVID-19 Pandemic, China, and Global Power Shifts: Understanding the Interplay and Implications.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Globalization With Chinese Characteristics: The Case of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by P. A. B. Duarte, F. J. B. S. Leandro, and E. M. Galán, 153–165. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hikvision. 2022. “Forças de Segurança de Roraima Utilizam Câmeras Da Hikvision Para Segurança Pública Em Zona de Fronteira.” Hikvision (blog). January 17, 2022. https://www.hikvision.com/pt-br/newsroom/ latest-news/2022/forcas-de-seguranca-de-roraima-utilizam-cameras- da-hikvision/.

Huawei. 2018a. “Campinas Reforça Parceria Com a Huawei Para Implementar Soluções de Segurança.” Huawei (blog). December 14, 2018. https://www.huawei.com/br/news/br/2018/dezembro/campinas- reforca-parceria-com-a-huawei.

Huawei. 2018b. “South Atlantic Inter Link Connecting Cameroon to Brazil Fully Connected.” Huawei (blog). September 6, 2018. https:// www.huawei.com/en/news/2018/9/south-atlantic-inter-link.

Huawei. 2022. “TIM Brasil and Huawei Sign MoU to Transform Curitiba Into the Country’s First ‘5G City.’.” Huawei (blog). March 4, 2022. https://www.huawei.com/en/news/2022/3/mou-tim-5g-city-2022.

Hulkó, G., J. Kálmán, and A. Lapsánszky. 2025. “The Politics of Digital Sovereignty and the European Union’s Legislation: Navigating Crises.” Frontiers in Political Science 7, no. February: 1548562. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpos.2025.1548562.

Hussain, F., Z. Hussain, M. I. Khan, and A. Imran. 2024. “The Digital Rise and Its Economic Implications for China Through the Digital Silk Road Under the Belt and Road Initiative.” Asian Journal of Comparative Politics 9, no. 2: 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/20578

Infodefensa.com. 2019. “Uruguay Blinda Con 1.000 Cámaras de Vigilancia La Frontera Con Brasil.” Infodefensa.Com (blog). February 23, 2019. https://www.infodefensa.com/texto-diario/mostrar/3166470/ uruguay-blinda-1000-camaras-vigilancia-frontera-brasil.

Ionova, A. 2020. “Brazil Takes a Page From China, Taps Facial Recognition to Solve Crime.” The Christian Science Monitor (Blog). February 11, 2020. https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Americas/ 2020/0211/Brazil-takes-a-page-from-China-taps-facial-recognition- to-solve-crime.

Jenkins, R. 2017. “China and Latin America.” In American Hegemony and the Rise of Emerging Powers: Cooperation or Conflict, edited by S. S. Regilme and J. Parisot, 182–197. Routledge.

Jiang, M., and K.-W. Fu. 2018. “Chinese Social Media and Big Data: Big Data, Big Brother, Big Profit?” Policy & Internet 10, no. 4: 372–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.187.

Law, N. 2023. “China’s Digital Influence in Latin America and the Caribbean: Implications for the United States and the Region.” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs 6, no. 7: 84–97. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/ JIPA/Display/Article/3540684/chinas-digital-influence-in-latin-ameri ca-and-the-caribbean-implications-for-th/.

Li, H. 2007. “China’s Growing Interest in Latin America and Its Implications.” Journal of Strategic Studies 30, no. 4–5: 833–862. https:// doi.org/10.1080/01402390701431972.

Majerowicz, E., and M. H. Carvalho. 2024. “China’s Expansion Into Brazilian Digital Surveillance Markets.” Information Society 40, no. 2: 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2024.2315880.

Makarov, I., and A. Sokolova. 2016. “The Eurasian Economic Union and the Silk Road Economic Belt: Opportunities for Russia.” International Organisations Research Journal 11, no. 2: 40–57. https://doi.org/10. 17323/1996-7845-2016-02-40.

Malena, J. 2021. The Extension of the Digital Silk Road to Latin America: Advantages and Potential Risks. Council on Foreign Relations; Brazilian Center for International Relations. https://cdn.cfr.org/sites/default/ files/pdf/jorgemalenadsr.pdf.

Maniscalco, M. L. 2006. “Netpolitik: ‘Internet’ e il Nuovo Spazio Politico Internazionale.” In Spazi e Politica Nella Modernità Tecnologica, edited by B. Consarelli, 15–33. Firenze University Press.

Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovações. 2022. Estratégia Brasileira Para a Transformação Digital (E-Digital). Ciclo 2022–2026. Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos do Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovações. https://www.gov.br/mcti/pt-br/acompanhe-o- mcti/transformacaodigital/estrategia-digital.

Ministério das Relações Exteriores. 2023. “Acordos Assinados Pelo Setor Privado e Por Entes Públicos Brasileiros Por Ocasião Da Visita Do Presidente Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva à República Popular Da China.” Ministério Das Relações Exteriores (blog). April 14, 2023. https://www. gov.br/mre/pt-br/canais_atendimento/imprensa/notas-a-imprensa/ acordos-assinados-pelo-setor-privado-e-por-entes-publicos-brasileiro s-por-ocasiao-da-visita-do-presidente-luiz-inacio-lula-da-silva-a-repub lica-popular-da-china.

Ministério das Relações Exteriores. 2024. People’s Republic of China. Ministério Das Relações Exteriores, January 9, 2024. https://www.gov. br/mre/en/subjects/bilateral-relations/all-countries/people-s-republic- of-china.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2021. “China-CELAC Joint Action Plan for Cooperation in Key Areas (2022–2024).” https://www.fmprc.gov. cn/mfa_eng//wjb_663304/zzjg_663340/ldmzs_664952/xwlb_664954/ 202112/t20211207_10463459.html.

O Globo. 2024. Veja a Lista Dos 37 Acordos Assinados Entre o Brasil e a China Durante a Visita de Xi Jinping a Brasília. O Globo, November 20, 2024. https://oglobo.globo.com/economia/noticia/2024/11/20/veja-a- lista-dos-37-acordos-assinados-entre-o-brasil-e-a-china-durante-a-visit a-de-xi-jinping-a-brasilia.ghtml.

Oliveira, H. A. 2010. “Brasil e China: Uma Nova Aliança Não Escrita?” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 53, no. 2: 88–105. https://doi. org/10.1590/S0034-73292010000200005.

Parzyan, A. 2021. China and Eurasia: Rethinking Cooperation and Contradictions in the Era of Changing World Order, edited by M. D. Sahakyan and H. Gärtner. Routledge.

Paulo, F. D. S. 2019. Bancada Do PSL Vai à China Conhecer Sistema Que Reconhece Rosto de Cidadãos F. D. S. Paulo, January 16, 2019. Folha de São Paulo. https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2019/01/bancada-do-psl- vai-a-china-importar-sistema-que-reconhece-rosto-de-cidadaos.shtml.

Pohle, J., and T. Thiel. 2020. “Digital Sovereignty.” Internet Policy Review 9, no. 4: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1532.

Presidência da República. 2023. Lula: Relação Do Brasil Com a China Chega a Outro Patamar. Presidência Da República. (blog), April 15, 2023. https://www.gov.br/planalto/pt-br/acompanhe-o-planalto/noticias/ 2023/04/lula-relacao-do-brasil-com-a-china-chega-a-outro-patamar.

Reconnecting Asia. 2021. Mapping China’s Digital Silk Road. Reconnecting Asia, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 19, 2021. https://reconasia.csis.org/mapping-chinas-digital-silk-road/.

Referência, A. 2023. “Deputado Cita ‘Risco à Soberania Nacional’ e Questiona a Presença Da Huawei No Brasil.” A Referência, June 28, 2023. https://areferencia.com/americas/deputado-cita-risco-a-sober ania-nacional-e-questiona-a-presenca-da-huawei-no-brasil/.

Reuters. 2018. China’s Didi Chuxing Buys Control of Brazil’s 99 Ride- Hailing App. Reuters, January 4, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/artic le/us-99-m-a-didi-idUSKBN1ES0SJ/?msclkid=96fc25cfb69b11ec9ed3 33a6ea0a543d.

Reuters. 2019. ‘Safe Like China’—In Argentina, ZTE Finds Eager Buyer for Surveillance Tech. Reuters, July 5, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/ article/world/safe-like-china-in-argentina-zte-finds-eager-buyer-for- surveillance-tech-idUSKCN1U00Z7/.

Reuters. 2023. Chinese Investment in Brazil Plunges 78% in 2022, Hits Lowest Since 2009. Reuters, August 29, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/ world/china/chinese-investment-brazil-plunges-78-2022-hits-lowest- since-2009-2023-08-29/.

Roy, D. 2023. “China’s Growing Influence in Latin America.” Council on Foreign Relations (blog). June 15, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/backg rounder/china-influence-latin-america-argentina-brazil-venezuela- security-energy-bri.

Rubiolo, F., and G. Fiore. 2024. “Balancing Continuity and Adjustments in Brazil’s Foreign Policy Towards China: A Comparative Approach Between Bolsonaro and Lula’s Third Term.” JANUS 15, no. no2, TD 1: 101–121. https://doi.org/10.26619/1647-7251.DT0324.5.

Sciacovelli, A. L. 2023. “Cybersecurity Challenges Between the EU and China and the Way Forward: Thoughts and Recommendations.” In China and Eurasian Powers in a Multipolar World Order 2.0, 202–211. Routledge.

Shen, H. 2018. “Building a Digital Silk Road? Situating the Internet in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” International Journal of Communication 12: 2683–2701. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/ view/8405/2386.

Su, Z., X. Xu, and X. Cao. 2022. “What Explains Popular Support for Government Monitoring in China?” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 19, no. 4: 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2021.1997868.

Tele.Síntese. 2018. Concluída a Construção Do Cabo Submarino Que Liga Brasil a Camarões. Tele.Síntese. (blog), September 6, 2018. https:// telesintese.com.br/concluida-a-construcao-do-cabo-submarino-que- liga-brasil-a-camaroes/.

Tele.Síntese. 2024. Fundo Firmado Entre Brasil e China Indica Incentivos à Infraestrutura Digital. Tele.Síntese, August 20, 2024. https://www. telesintese.com.br/fundo-firmado-entre-brasil-e-china-indica-incen tivos-a-infraestrutura-digital/.

TeleGeography. 2024. “Submarine Cable Map.” Submarine Cable Map, August 5, 2024. https://www.submarinecablemap.com/.

Teletime. 2018. Parceria Entre Oi e Huawei Foca Em Monitoramento Para Smart Cities. Teletime. (blog), October 16, 2018. https://teletime. com.br/16/10/2018/parceria-entre-oi-e-huawei-foca-em-monitorame nto-para-smart-cities/.

Teletime. 2021. União Europeia Inaugura Cabo Submarino EllaLink, Entre Brasil e Portugal. Teletime. https://teletime.com.br/01/06/2021/ uniao-europeia-inaugura-cabo-submarino-ellalink-entre-brasil-e- portugal/.

The New York Times. 2019. Made in China, Exported to the World: The Surveillance State. New York Times, April 24, 2019. https://www.nytim es.com/2019/04/24/technology/ecuador-surveillance-cameras-police- government.html.

Tomé, L. 2023. The Palgrave Handbook of Globalization With Chinese Characteristics: The Case of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by

- A. B. Duarte, F. J. B. S. Leandro, and E. M. Galán, 67–90. Palgrave Macmillan.